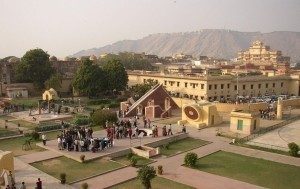

The Jantar Mantar Astronomical Garden of Jaipur, Rajasthan is a collection of nineteen architectural astronomical instruments, built by the Rajput king Sawai Jai Singh, who was fascinated by the heavens and is often called the Newton of the East.

The Jantar Mantar Astronomical Garden of Jaipur, Rajasthan is a collection of nineteen architectural astronomical instruments, built by the Rajput king Sawai Jai Singh, who was fascinated by the heavens and is often called the Newton of the East.

It was completed in 1734 CE after several years of studying foreign observatories and the works of Ptolomy, de Hire, Flamsteed and Newton, among others. It is a UNESCO World Heritage site and includes the world’s largest stone sundial (although not the largest sundial, see my other blog pieces). As a sundial maker I’ve wanted to go for ages, and finally this November I made the pilgrimage. I’ll be describing some of the sundials in detail in later posts, but here is a summary of the garden, and the science behind it. It does get a bit complicated, so bear with…

It is worth spending a bit of time explaining how the Indian Astronomers of the day saw the cosmos. The Earth is a sphere set in the middle of an enormous heavenly sphere, on the inner surface of which the stars are situated. The heavenly sphere rotates on its axis, which runs through the poles, once a day, and this accounts for the daily motion of the stars.

The Earth is immovably fixed in the centre of the universe, and surrounding the Earth, but within the heavenly sphere, are the orbits of the nine planets (not as we know them, but Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, the Sun and the Moon).

The Jantar Mantar astronomy garden’s instruments were used for finding the stars and planets by the three main classical celestial coordinate systems: the horizon-zenith system, the equatorial system and the ecliptic system.

The horizontal-zenith, or altitude-azimuth system is based on the position of the observer on Earth, which revolves around its own axis once per sidereal day (23 hours, 56 minutes and 4.091 seconds) in relation to the “fixed” star background. The positioning of a celestial object by the horizontal system varies with time, but is a useful coordinate system for locating and tracking objects for observers on Earth. This system is still popular among amateur astronomers today.

The equatorial system is centered at Earth’s centre, but fixed relative to distant stars and galaxies. The coordinates are based on the location of stars relative to Earth’s equator if it were projected out to an infinite distance. The equatorial describes the sky as seen from the solar system, and modern star maps almost exclusively use equatorial coordinates. This is the normal coordinate system for most professional and many amateur astronomers.

The ecliptic system is based on the plane of the Earth’s orbit around the sun. The ecliptic system was the principal coordinate system for ancient astronomy and is still useful for computing the apparent motions of the Sun, Moon, and planets

Today astronomers also use the galactic system (which isn’t described at the Jantar Mantar) This uses the approximate plane of our galaxy as its fundamental plane. The solar system is still the centre, and the zero point is defined as the direction towards the galactic centre. Galactic latitude resembles the elevation above the galactic plane and galactic longitude determines direction relative to the centre of the galaxy.

Although the basic Earth centric system has been proven wrong, the Jantar Mantar is still extremely accurate at measuring the position and path of heavenly bodies. If you ever visit Rajasthan, do go to the Jantar Mantar, if for no other reason than to wonder at the size of these magnificent instruments.

Finally; Jantar means ‘instrument’ and Mantar comes from the same route as ‘mantra’ meaning a ‘formula or calculation’. So Jantar Mantar approximately means an ‘Instrument of Calculation’